On one particularly warm morning early this year, I drove north along Queen Ka'ahumanu highway towards Kiholo Bay, a seasonal Hawaiian home for humpback whales. I arrived at Kiholo before the sun rose over Mauna Kea, but signs of the world waking were already multiplying by the minute: birds squawking in the trees; mongooses anxiously darting in and out of the brush; sleepy, tanned people emerging from tents at the beachside campground; and whales surfacing at the edge of the bay.

Whales! Whales were the reason I was there, and three of them seemed to greet me from a distance — perhaps a mile offshore — with tiny pinpricks of breath and spray popping above the gentle line where sea met sky. I smiled, excited that I spotted the whales so quickly, and turned my attention to finding Jeffory (who would be my whale guide for the morning) in the campground.

I found Jeffory at a picnic table along the bay. He and I spent a few minutes organizing gear — snorkels, fins, kayak pedal drives, water, snacks, hats, GoPro, etc, before walking down to the water to load the double-kayak in the water.

Once in the kayak and past the shore break, we paused for a moment. Jeffory said a short blessing: for our safety on the water, for the openness of whales to come towards us, and for the gift of the ocean and Earth (it was beautiful and really just amazing). Then we were off, paddling away, away, away from shore and towards the whales lingering outside the wide mouth of the bay (~2 miles wide, Kiholo is the second largest bay on the Big Island).

My sense of time was entirely distorted on the water, but it must have taken 45 minutes to reach near where we had seen the whales from shore. Once outside the bay, I felt especially small compared to the ocean swells — calm but substantial — that raised the kayak up and down. We paddled quietly, beholden to the rhythm of the swells, waiting for a glimpse of the whales surfacing.

One of the strangest aspects of the experience — which I noticed immediately — was that from above the ocean surface, it’s nearly impossible to tell if a whale is twenty feet or two hundred meters away from you. Their only giveaway is breaking the surface (the whoosh of a breath or the splash of a breech or the eerie calm, stagnant top layer of water left after they dive somewhat of a vacuum effect). They are silent, elegant, and simply surprising.

We paused paddling to sit and wait to relocate them. I searched the water at incremental distances, radiating outward from the kayak: 20 meters, 50 meters, 100 meters. The minutes ticked by. But no sooner had I given up, and anxiously decided that the whales must be right below us, did I hear a faint whoosh in the distance. About 100 meters south one, two, three whales surfaced, headed back towards the mouth of the bay.

My initial instinct was to pedal toward them, but Jeffory quickly explained why that was a lost cause: 1) the whales are far faster than the kayak, and they would go and do as they please — in effect, they had to want to come near the humans for them to be near the humans; 2) if we aimed for where the whales “were” we wouldn’t be able to meet them where they were “going to be” (duh, I realized later: physics, interception points, and such). So what did we do? We paddled slightly southwest in the direction they were headed (towards the mouth of the bay) and then waited again, patiently, as the sun rose over Mauna Kea.

Only a few minutes later the whales reappeared, much closer this time: a momma, a few-day-old baby, and an “escort” (sort of a protector whale that keeps an eye on the pair). Their smooth backs glided along the surface, the heave of their breath cracking the still air, tiny barnacles scattered like stars along their school-bus-sized bodies. I sat in awe. Jeffory queued me to put on my snorkel, mask, and fins. If the whales decided to come closer, we’d be able to slip into the water and swim with them from a safe (but remarkably intimate) distance.

We kept moving, and settled into a rhythm in the kayak: paddle, wait, observe, paddle, wait, observe. Intermittently, Jeffory would gently slip off the kayak, under the water, to hear if the whales were singing. The whales continued to come closer and closer to us. I wondered: were they curious and trusting or simply oblivious? (I highly doubted the latter, but it did cross my mind.) Soon they were among us. Or, more accurately: we were among them.

From the water, Jeffory signaled me to quietly slide off the kayak. The water was deep and impeccably clear— we were far off the edge of the reef. I adjusted my mask and looked straight ahead. In front of me, headed directly towards me… the whales: the momma positioned with the baby above her back, closer to the surface; the escort far below the momma, just a shadow in the depths. They moved towards us, dead on, so close I could have reached them in a few strokes, then cut a turn alongside us as if to nod us hello.

It’s taken me months to process that first moment in the water with them — their power, their wonder, their sacredness. Mostly I remember how time froze, how in awe I was, and how deeply humbled I was by their scale and movement. I have always loved Mary Oliver’s poem “Wild Geese,” which closes with the lines “the world offers itself to your imagination / calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting / over and over announcing your place / in the family of things.” But it wasn’t until meeting the eye gaze of the momma whale — for real — that I understood in my body what being part of the family of things meant.

No sooner did the moment come than did it pass. Within a few minutes we could no longer see the whales below the surface. We pulled ourselves back into the kayak and returned to our rhythm: paddle, wait, observe. We did slip in the water a few more times with them, each different experiences at different distances, but nothing compared to that initial encounter.

Once the water got siltier and visibility dropped, we stuck to our vantage point in the kayak, and followed them (or they followed us) across the length of the bay’s opening. We tag teamed with them for hours as they cruised past us, dove under us, and doubled back on us. For Jeffory, who would spend the rest of the winter season visiting this group of whales; these hours were (quite literally) a foundational relationship bonding exercise with these highly intelligent mammals.

Late in the morning, we neared the North end of the bay’s opening. The whales surfaced a few times more and then, as if as content with the extent of the experience as we were, deliberately turned due west and charted out to sea.

In the moment, I was left with the raw emotion of the experience and a calm paddle back to shore, the whales' spouts growing ever more distant behind us. In the weeks and months to come, though, I found myself left with so much more: an experience with nature that was so serene and powerful it had imprinted on my consciousness… a memory that I return to frequently in the hustle and bustle of everyday life… and a reminder that as much as we humans have pulled away from the animal kingdom, there are moments we can still find ourselves fully enveloped in the family of things.

Cassidy, California

January 2021

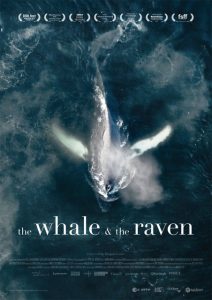

Sind Wale Individuen mit der Fähigkeit zur Selbstwahrnehmung und Intelligenz? Janie Wray und Hermann Meuter sind fest davon überzeugt. Seit 15 Jahren dokumentieren die beiden Wal-Forscher das Verhalten von Orcas, Buckel- und Finnwalen an der Westkü

Sind Wale Individuen mit der Fähigkeit zur Selbstwahrnehmung und Intelligenz? Janie Wray und Hermann Meuter sind fest davon überzeugt. Seit 15 Jahren dokumentieren die beiden Wal-Forscher das Verhalten von Orcas, Buckel- und Finnwalen an der Westkü